If you’re wondering why this is part 4.1 instead of part 4, and why I’m not talking about continuing to build the local jbc, it’s because explaining Bitcoin’s Proof of Work difficulty at a somewhat lower level takes a lot of space. So unlike what this title says, this post in part 4 is not how to build a blockchain. It’s about how an existing blockchain is built.

My main goal of the part 4 post was to have one section on the Bitcoin PoW, the next on Ethereum’s PoW, and finally talk about how jbc is going to run and validate proof or work. After writing all of part 1 to explain how Bitcoin’s PoW difficulty, it wasn’t going to fit in a single section. People, me included, tend get bored in the middle reading a long post and don’t finish.

So part 4.1 will be going through Bitcoin’s PoW difficulty calculations. Part 4.2 will be going through Ethereum’s PoW calculations. And then part 4.3 will be me deciding how I want the jbc PoW to be as well as doing time calculations to see how long the mining will take.

The sections of this post are:

- Calculate Target from Bits

- Determining if a Hash is less than the Target

- Calculating Difficulty

- How and when block difficulty is updated

- Full code

- Final Questions

TL;DR

The overall term of difficulty refers to how much work has to be done for a node to find a hash that is smaller than the target. There is one value stored in a block that talks about difficulty — bits. In order to calculate the target value that the hash, when converted to a hex value has to be less than, we use the bits field and run it through an equation that returns the target. We then use the target to calculate difficulty, where difficulty is only a number for a human to understand how difficult the proof of work is for that block.

If you read on, I go through how the blockchain determines what target number the mined block’s hash needs to be less than to be valid, and how that target is calculated.

Other Posts in This Series

- Part 1 — Creating, Storing, Syncing, Displaying, Mining, and Proving Work

- Part 2 — Syncing Chains From Different Nodes

- Part 3 — Nodes that Mine

- Part 4.2 — Ethereum Proof of Work Difficulty Explained

Calculate Target from Bits

In order to go through Bitcoin’s PoW, I need to use the values on actual blocks and explain the calculations, so a reader can verify all this code themselves. To start, I’m going to grab a random block number to work with and go through the calculations using that.

>>>import random >>> random.randint(0, 493928) 111388

Block number 11138 it is! Back in time to March of 2011 we go.

We’re going to start with assigning variables with the bits and difficulty values from the block, as well as the hash, so we can test its validity at the end.

>>> bits = '453062093'

>>> difficulty = float('55,589.52'.replace(',',''))

>>> block_hash = '00000000000019c6573a179d385f6b15f4b0645764c4960ee02b33a3c7117d1e'

Next part shows how to go from the bits field to the target. There are at least two different ways to do this — the first involves string manipulation and string to integer conversion, and the other uses bit manipulation.

For the first string manipulation part, we convert the bits string to an integer and then to a hex string. The first two characters of the hex_bits string are in one variable, which I call shift, and the remaining six are called the value. From there, we use those values in the integer equation that will calculate the integer value of the target, which we can convert to a hex string to look at how pretty it is!

Note that ‘L’ on the back of the target and hex(target) is only Python telling you that the numbexr is too long to be stored as an int, and that it’s stored as a long.

>>> hex_bits = hex(int(bits)) >>> hex_bits '0x1b012dcd' >>> shift = '0x%s' % hex_bits[2:4] >>> shift '0x1b' >>> shift_int = int(exponent, 16) 27 >>> value = '0x%s' % hex_bits[4:] >>> value '0x012dcd' >>> value_int = int(coefficient, 16) 77261 >>> target = value_int * 2 ** (8 * (shift_int - 3)) >>> target 484975157177710342494716926626447514974484083994735770500857856L >>> hex_target = hex(target) >>> hex_target '0x12dcd000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000L'

It seems a little fake when we slice a string to calculate the target like we do above. When looking through the c++ bitcoin implementation, it shows the other, more technical, main method of using bits to calculate target. Here’s the Python implementation.

I’ll go through the lines and print values here to show a little better what’s going on. One thing to know before reading is that a character in a hex string represents 4 bits. So when we shift the bits variable by 24 bits with bits >> 24 that affectively removes the last 6 characters of the hex string leaving the first two. To get the value variable, we use the bitwise and operator & to have the final 23 bits be the value. The 23 bits is usually (defined by the number of bits in 0x7fffff) the final 6 characters of the hex string,

Now, the 8 * (shift - 3) value determines how many bits we’re going to shift value over. In this case, it’s determined to be 192 bits. If we divide the 192 by 4, we’ll have the number of zeros characters that will be behind the value in the hex string representation of the target number. You’ll see that it’s 48 zeros. Another thing to think of if this is confusing is that value << y is the same as value * 2**y. That’s how the equations are related.

>>> bits = '453062093'

>>> hex(int(bits))

'0x1b012dcd'

>>> shift = bits >> 24

>>> shift

27

>>> hex(shift)

'0x1b'

>>> value = bits & 0x007fffff

>>> hex(value)

'0x12dcd'

>>> 8 * (shift - 3)

192

>>> 192 / 4 #each character in a hex string represents 4 bits

48

>>> value <<= 8 * (shift - 3)

>>> hex(value)

'0x12dcd000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000L'

>>> hex(value).count('0') - 1 #don't count the leading zero

48

The full function version of this is only a few lines long.

>>> def get_target_from_bits(bits): ... shift = bits >> 24 ... value = bits & 0x007fffff ... value <<= 8 * (shift - 3) ... return value ... >>> target = def get_target_from_bits(int(bits)) >>> hex(target) '0x12dcd000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000L'

So nice. If you look way above to see the string manipulation code it’s way more confusing and has so many extra lines than the function above. It’s great to go through both to really understand the meaning, but then stick with the simple one. Moving on.

Determining if a Hash is less than the Target

As always it seems, there are two simple ways to see if a block’s hash is valid according to the target. The first way is to use full, 64 character, 256 bit, hex strings and compare those. This works great since we’ll be able to see this easily eye to eye. To show this is the case, we’re going to pad the hex_target with the zeros to fill all 64 characters.

>>> hex_target = hex(target)

>>> len(hex_target)

56

>>> len(hex_target[2:-1]) #[2:-1] removes the leading '0x' and ending 'L'

53

>>> num_padded_zeros = 64 - hex_target_len

>>> num_padded_zeros

11

>>> padded_hex_target = "0x%s%sL" % ('0' * (64-num_padded_zeros), hex_target[2:-1])

>>> padded_hex_target

'0x0000000000012dcd000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000L'

Finally, we want to verify that the block’s hash is less than the target. And also, since strings can be considered less than or greater than, we’ll go with that.

>>> len(block_hash) 64 >>> padded_block_hash = '0x%sL' % block_hash >>> padded_block_hash 0x00000000000019c6573a179d385f6b15f4b0645764c4960ee02b33a3c7117d1eL >>> padded_hex_target 0x0000000000012dcd000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000L >>> assert padded_block_hash < padded_hex_target >>>

In this case, you’ll see the hex target is larger than the block’s hash. Comparing which string is larger is as simple as either < or >. If you’re wondering how Python can determine that the characters like 'f' > '1', see the questions below.

The other way to confirm is by using the integers for both values. But as you’ll see, it’s very difficult, if not impossible, to eyeball which is value larger, and how much larger one value is to than the other.

>>> block_hash_int = int(block_hash, 16) >>> block_hash_int 41418456048005639864974238890271849696605172030151526454492446L >>> target 484975157177710342494716926626447514974484083994735770500857856L >>> assert(block_hash_int < target) >>> target - block_hash_int 443556701129704702629742687736175665277878911964584244046365410L

Those ints are so huge that looking at one by itself is pretty much impossible to know if it’s easy or difficult to be lower than. But since block_hash_int is lower than target int by one character, you can see that’s the case. When you subtract those two giant numbers you get another giant number.

Both are valid methods, but being able to look at the hex strings is better than looking at the integers. But really, when the code is running, there’s no real benefit to pick one over the other.

Calculating Difficulty

The most important part of difficulty is to remember from above that difficulty is simply a human representation of the target. I talked about how integer values of targets are pointless since it’s hard to humanly compare two values that are giant integer. Likewise, it’s tough to compare two targets to each other using the hex strings. The difficulty values in a block are to make that easier.

Below, difficulty_one_target is defined as the easiest allowed target value. To calculate the difficulty of another block, we simply divide the difficulty_one_target by the target we’ve calculated using bits. You’ll see that difficulty_one_target will be larger than any other target number since targets go lower with more difficulty. When you divide the larger numerator by a smaller denominator, you’ll have a greater than one value.

>>> difficulty_one_target = 0x00ffff * 2**(8*(0x1d - 3)) >>> difficulty_one_target 26959535291011309493156476344723991336010898738574164086137773096960L #calculated using >>> pad_leading_zeros(hex(difficulty_one_target)) #pad_leading_zeros is function defined below '0x00000000ffff0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000' >>> calculated_difficulty = difficulty_one_target / float(target) #float() to make it decimal devision 55589.518126868665 #this is the same as the difficulty on the block. >>> allowed_error = 0.01 >>> assert abs(float(block_difficulty) - calculated_difficulty) <= allowed_error >>>

Feel free to go back and read this over slowly. It took me a long time to figure out the relationship between bits, difficulty, and target. Whether we need ints, hex values, or strings to verify. There are a bunch of ways to do this, and hopefully I’ve listed them all here.

How and when block difficulty is updated

The final big part of Bitcoin’s proof of work is to show how and when the difficulty is changed. Pretty much every post on this topic will say that the chain will recalculate the required new difficulty every 2016 blocks. But they don’t dive too deep at all into the topic. That’s what I’m going to do here.

The first part I have to start with is how to start with a target, and go back to bits. The get_bits_from_target function takes a target, calculates the the highest ranking bit that’s set and uses that to calculate the size. Knowing the size, we shift the target all the way down, removing the zeros we don’t need anymore, and finally put the value of size at the front of the bits so we keep it stored.

>>> bits = '403088579' >>> hex(int(bits)) '0x1806a4c3' >>> target = get_target_from_bits(int(bits)) >>> hex(target) '0x6a4c3000000000000000000000000000000000000000000L' >>> def get_bits_from_target(target): ... bitlength = target.bit_length() + 1 #look on bitcoin cpp for info ... size = (bitlength + 7) / 8 ... value = target >> 8 * (size - 3) ... value |= size << 24 #shift size 24 bits to the left, and taks those on the front of compact ... return value ... >>> bits = get_bits_from_target(target) >>> bits 403088579L >>> hex(bits) '0x1806a4c3L

They match, so we know the code correctly returns a target to bits.

Time to show how to calculate the next block’s bits for an actual set of blocks on the blockchain. For the example here, I’m going to say we’ve just received block #405215 and are looking to mine block #405216. Looking back 2016 blocks, 403200 will be considered the starting block.

We have a starting target calculated from that block’s bits. We use that difficulty for the next 2016 blocks. When we come to the 2017th block after the first, we calculate the time in seconds it took for us to go from the original block to the 2016th. We divide that by the 2016 block in seconds, multiply the current target by that value, and then calculate the new bits from that target.

TARGET_TIMESPAN = 1209600 def change_target(prev_bits, starting_time_secs, prev_time_secs): old_target = get_target_from_bits(int(prev_bits)) time_span = prev_time_secs - starting_time_secs time_span_seconds = int(time_span.total_seconds()) new_target = old_target new_target *= time_span_seconds new_target /= TARGET_TIMESPAN return new_target #starting_block is the initial block on this 2016 block runtime #403200 starting_block_timestamp = '2016-03-18 09:07:48' #timestamp on block starting_block_time_seconds = datetime.datetime.strptime(starting_block_timestamp, '%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S') #prev_block is the block right before the difficulty conversion #405215 prev_block_bits = '403088579' #bits on block prev_block_timestamp = '2016-04-01 06:24:09' #timestamp on block prev_block_time_seconds = datetime.datetime.strptime(prev_block_timestamp, '%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S') calculated_new_target = change_target(prev_block_bits, starting_block_time_seconds, prev_block_time_seconds) calculated_new_bits = get_bits_from_target(calculated_new_target) #new_block is the first block of the next block #405216 new_bits = '403085044' new_target = get_target_from_bits(new_bits) print hex(calculated_new_target) print hex(new_target) print hex(calculated_new_bits) print hex(int(new_bits))

Which spits out

Calculated new target: 0x696f4a7b94b94b94b94b94b94b94b94b94b94b94b94b94bL New target from block: 0x696f4000000000000000000000000000000000000000000L Calculated new bits: 0x180696f4L New bits from block: 0x180696f4

The calculated new target is very specific. But we don’t really care about making sure a block’s hash is that specific. They only need to know the leading 23 bits. Ditch the rest of them, shove them down, and throw the shift on the front.

Full Code

I was going to copy and paste the giant amount of code I wrote above so you could copy and paste it and run it yourself. But that would take up too much space. So here’s a gist where you’ll be able to see everything.

Final Questions

Congrats if you’ve made it this far! Here’s a set of questions that I had when learning and writing this. If you have any more, get in contact and I’ll throw and answer on.

Why are the hex values only strings?

Because hex values are only representations of integers. If you’re looking to see the hex value of an integer, we need a string to look at the different base 16 values. Look at the Python definition of hex() slightly more info.

How can a string comparison know that 'f' > '9'?

In memory, characters are stored as unicode values. So when you compare two characters, the one with the larger unicode value is shown as being the biggest. Note that ASCII also has the same values as unicode for 0-127. When comparing strings, they go through each character one by one and whichever has the largest value first wins the race.

>>> ord('f')

102

>>> ord('a')

97

>>> ord('b')

98

>>> ord('9')

57

>>> ord('1')

49

>>> ord('2')

50

>>> ord('a')

97

>>> ord('b')

98

>>> ord('f')

102

>>> 'f' > 'a'

True

>>> 'a' > '1'

True

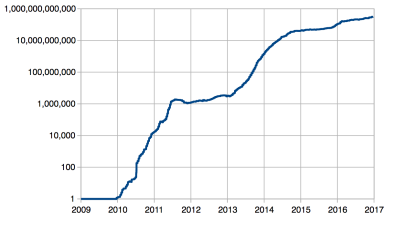

How has Bitcoin difficulty changed over time?

There are a bunch of sites that have interactive graphs showing the change over time; quick google will find one. But, here’s the pic from Bitcoin’s actual Wikipedia page that shows how that difficulty number has changed over time.

What’s the deal with mid 2011 to beginning of 2013 difficulty being flat?

Look at this screenshot from Bitcoin.com for the time period of 2011 and 2013.

A giant spike in price all the way up to an astonishing $29 a coin that crashed until the beginning of 2013 where it starts flying up again. I’ll go ahead and say there’s a nice correlation there where miners saw the crash and said screw it, stopped their mining, and left fewer nodes trying to mine a new block. Fewer nodes means the longer it takes to find a valid hash so we had to keep difficulty down.

Does a larger bit value imply a larger difficulty?

Nope. Remember, bit values are stored so we can split it into two numbers used to calculate the target. When looked at as an integer, it’s definitely not comparable.

If you want examples, look at the couple blocks listed in the code above. Comparing blocks 0 and 32256, you’ll see opposite difference in bits and difficulty.

How is the header hash calculated?

By smashing values together. Take a look here and you’ll see more about it.

I see people mentioning we only calculate new bits from 2015 blocks and not 2016. What’s that mean?

You’ll see that a lot when looking at other posts. What this means is if we included all 2016 blocks in a set, we’d start with the timestamp before the start of a new 2016 set of blocks since that’s says when nodes started trying to find the next block.

This doesn’t work out when you think of calculating the new bits for actual block 2017. If we took into account how long it took to mine the first 2016, we wouldn’t know that since we didn’t know when we started running the first miners.

Why didn’t you talk about how much time it takes to find a valid hash?

That’s a different topic. There’s some material on calculating that if there’s a single node doing the mining, but that’s tough to figure out unless you have a bigger amount of nodes. When I write the part for jbc’s difficulty, I’ll have tests to show time.

What’s your Twitter handle so I can follow you??

What if I only want to ask you a question?

Contact is a great way to do this. Just make sure you type your email correctly; I’ve gotten some emails before that I couldn’t reply to since that email address didn’t exist. Also feel free to comment on this post as well.

What’s next?

Part 4.2 about the Ethereum proof of work difficulty! It’s somewhat similar, but the target is calculated in a different way. Also, the time when difficulties change is different as well. Check out the chart that show difficulty over time to see what I mean.

After that, part 4.3 will be about how I want to calculate difficulty for jbc.

Hell, yeahs, thanks ant article !

I imaginne how much cup of coffee you needed to understand that by your self 😀

LikeLike