The great majority of the projects about machine learning or data analysis I write about here on Bigish-Data have an initial step of scraping data from websites. And since I get a bunch of contact emails asking me to give them either the data I’ve scraped myself, or help with getting the code to work for themselves. Because of that, I figured I should write something here about the process of web scraping!

There are plenty of other things to talk about when scraping, such as specifics on how to grab the data from a particular site, which Python libraries to use and how to use them, how to write code that would scrape the data in a daily job, where exactly to look as to how to get the data from random sites, etc. But since there are tons of other specific tutorials online, I’m going to talk about overall thoughts on how to scrape. There are three parts of this post – How to grab the data, how to save the data, and how to be nice.

As is the case with everything, programming-wise, if you’re looking to learn scraping, you can’t just read tutorials and think to yourself that you know how to program. Pick a project, practice grabbing the data, and then write a blog post about what you learned.

There definitely are tons of different thoughts on scraping, but these are the ones that I’ve learned from doing it a while. If you have questions, comments, and want to call me out, feel free to comment, or get in contact!

Grabbing the Data

The first step for scraping data from websites is to figure out where the sites keep their data, and what method they use to display the data on the browser. For this part of your project, I’ll suggest writing in a file named gather.py which should performs all these tasks.

That being said, there are a few ways you’ll need to look for to see how to most easily get the data.

Check if the site has an API First

A ton of sites with interesting data have APIs for programmers to grab the data and write posts about the interesting-ness of the site. Genius does this very nicely, except for the song lyrics of course.

And also if the site has an API, that means that they’re totally alright with programmers using their data, though pretty much every site doesn’t allow you to use its data to make money. Read their requirements and rules for using the site’s data, and if your project is allowed, API is the way to go.

Figure out the URLs of all the data

If there is no API, that means you’re going to have to figure out the urls where the site displays all the data you need.

A common type you’ll see is that the data is displayed using IDs for the objects. If you’ve done web development in something like Rails, you’ll know exactly how that works. In this case, there probably is an index page that has links to all the different pages you’re trying to scrape, so you’ll have two scraping requirements. And like I’ve said, each site is different, but just know that these are possible requirements to get all the data you want.

Check JSON loading of data

If the site doesn’t have an API and you’re still going to want the data, check to see if the page that shows the data you’re looking for is by using JSON. If the page loads and it takes a second or a flash for the text to show up, it’s probably using that JSON.

From there, right click the web page and click “Inspect” on Chrome to get the Developer Tools window to open, reload the web page, and check the Sources tab to see pages that end in .json. You’ll be able to see the URL it came from, then open a new tab and paste that URL and you’ll be able to see the JSON with your data!

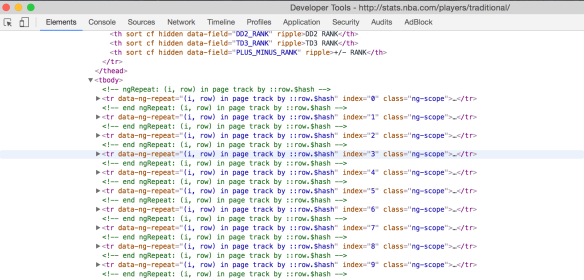

Quick example of how stats.nba.com generates their pages. If you just look at the HTML returned, you’ll see that it’s only AngularJS, meaning you can’t use the HTML to scrape the data. You’ll need to find the JS url that loads that data.

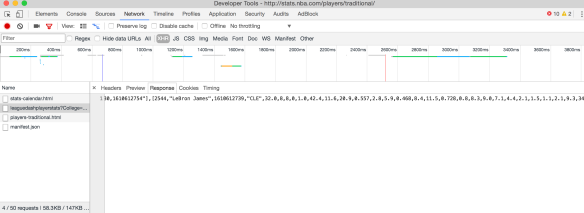

Looking at the network, I find a specific html file requested for over the Network.

Then, by reloading the page and checking the files under the Network tab, I find the url that generates the data for the page. As you can see, it’s just a JS variable that has all the data for the players.

I won’t list the URL specifically here, but there are ways to change it to grab the data that you’re looking for.

Fall back to HTML scraping

If the site you’re looking for data from doesn’t have an API or use JSON to load the data, you’re going to fall back to grabbing the HTML pages. Which is the only technique that people think of when imagining web scraping!

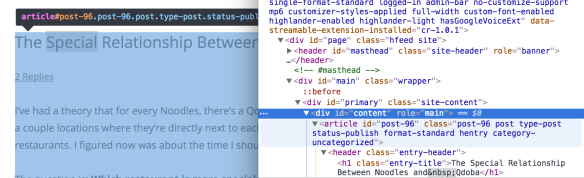

Like the JSON data, you’re going to have to use the Inspect feature of Chrome’s development tools, but in this case right click on the text that you’re trying to grab and analyze the classes and ids in order to grab that data.

For example, if you’re looking to scrape a WordPress blog to do something like sentiment analysis of the posts, you’ll want to do something like this:

As for other sites, I won’t go into exactly how that’s to be done because the classes and ids vary, but odds are it’ll be structured similarly with specific classes and ids for the data part of the page. Practice HTML scraping a couple sites and you’ll see how that part is.

Saving the Data

After you have the data saved using gather.py, you’ll need to write code that scrapes the data. In case you didn’t guess this, a good name for that file is scrape.py.

With this file, you’ll want to write the code that grabs the data and structures it for what you saved. How to save the data also depends on the type of scraping job you’re writing.

CSV is probably a fine type of database initially

There are two different types of scraping projects. First is just grabbing data that is consistent and doesn’t change that much over time. Like the PGA Tour stats I’ve scraped which change week by week for the current year but obviously don’t change when grabbing stats for every year in the past. Another example of this is how to get lyrics from Genius. Lyrics don’t change, and if you’re looking for other information about the songs, that doesn’t change much over time either.

If you’re getting this kind of data, don’t worry about setting up a DB to save the data. All types of this have a limited amount and frankly, test files are also quick to analyze the data.

Database is useful if you have data that keeps coming

On the other hand, if the data you’re looking to scrape is updated continuously, you’re probably going to want a DB to store the data, especially if you have a service (Heroku, Amazon, etc.) that runs your scraping code at certain times.

Another use for the DB is if you’re looking to scrape the data and then make a website that displays the data. Something like a script that checks Reddit comments to see how many Amazon products are mentioned and then displays them online.

And obviously the benefit of storing the data in a database rather than local files is that querying to compare data you scraped is much easier than having to load all your files into variables and then analyze the data. Like everything I’ve mentioned here, types of methods depends on the site, data, and information you’re trying to gather.

Be Nice

Scrape with header that has your name and email so company knows it’s you.

Some sites will get mad at you if you’re scraping their data. Even when the sites aren’t “nice”, you don’t want to do something “illegal”. An example of a way to do this:

import requests

from = "'From': %s" % 'contact@bigishdata.com'

headers = {'user-agent' : 'Jack Schultz, bigishdata.com, contact@bigishdata.com'}

html = requests.get(url, headers=headers)

You can look up other options for the request header, but make sure it’s the same and that people who look at their server’s logs know who you are, just in case they want to get in contact.

Make sure you don’t keep hitting the servers!!!!

When you’re writing and running gather.py make sure you’re testing it in a way that doesn’t continuously hit the servers to gather the data! I’m talking about using JSON and HTML. As for API, you’ll also want to make sure you’re not hitting the end points time and time again, especially since they track who’s hitting the API and most only allow a certain number of requests per time period.

Then when you’re running scrape.py, don’t hit their servers over and over as well. That script deals with gathering the data that you already got from their site.

Basically, the only time you should continuously hit the servers is when you’re running your final code that gets and saves the data / files from the site.

Gevent

Now if you’re needing to scrape data from a bunch of different web pages, Gevent is the python library to use that will help run request jobs concurrently so you’ll be able to hit the API, grab the JSON, or grab the HTML pages quicker. Since for the most part, the longest code is the kind that hits their servers and then wait for the file to be returned.

import gevent from gevent import monkey monkey.patch_all() ... #set the urls that you'll get the data from jobs = [gevent.spawn(gather_pages, pair[0], pair[1]) for pair in url_filenames] gevent.joinall(jobs)

Again, as long as you’re not going too quickly destroy their servers by asking for thousands of pages at once, feel free to use Gevent. Especially since most sites have more than 50 requests at once.

Practice, practice, practice

With all that said, and what is the case with everything, if you want to web scrape, you gotta practice. Reading so many of the tutorials is interesting and does teach you things, but if you want to learn, write the code yourself and search for tutorials that help solve your bugs.

And remember, be nice when grabbing the data.

Like this URL:

http://stats.nba.com/stats/leaguedashplayerstats?College=&Conference=&Country=&DateFrom=&DateTo=&Division=&DraftPick=&DraftYear=&GameScope=&GameSegment=&Height=&LastNGames=0&LeagueID=00&Location=&MeasureType=Base&Month=0&OpponentTeamID=0&Outcome=&PORound=0&PaceAdjust=N&PerMode=PerGame&Period=0&PlayerExperience=&PlayerPosition=&PlusMinus=N&Rank=N&Season=2016-17&SeasonSegment=&SeasonType=Playoffs&ShotClockRange=&StarterBench=&TeamID=0&VsConference=&VsDivision=&Weight=

LikeLike

Pingback: General Tips for Web Scraping with Python – Full-Stack Feed

Pingback: 2 – General Tips for Web Scraping with Python

Pingback: This Week in Data Science (May 16, 2017) – Be Analytics

Pingback: This Week in Data Science (May 16, 2017) – Cloud Data Architect

Pingback: This Week in Data Science (May 16, 2017) - biva

Pingback: This Week in Data Science (May 16, 2017) – Be Analytics

com/2017/05/11/general-tips-for-web-scraping-with-python/ […] […] Read more here: <a href="https://bigishdata.

LikeLike

Pingback: Web Scraping with Python — Part Two — Library overview of requests, urllib2, BeautifulSoup, lxml, Scrapy, and more! | Big-Ish Data

Very well written post… and a bit cathartic as a newbie programmer who has experienced all the roadblocks you point out. I will add a few more:

Basic “Learning How To Scrape” tutorials are usually reliably but get you 50% of the way there.

The more valuable the information, the more likely it is to be protected (LinkedIn, Yelp, Google Reviews). More advanced HTML scraping tutorials will not work out of the gate, as sites change their coding often. As a newbie, this has been the hardest part of “learning” to adjust to.

LinkedIn knows who you are and can block you / shut down your account with too many infractions. This is especially true on the free / low cost tier plans. Sales Navigator, which costs closer to $70/mo, will allow you to scrape much more information as it’s intended for higher volume sales activities.

LikeLike